Where Tampa’s Cuban Story Began

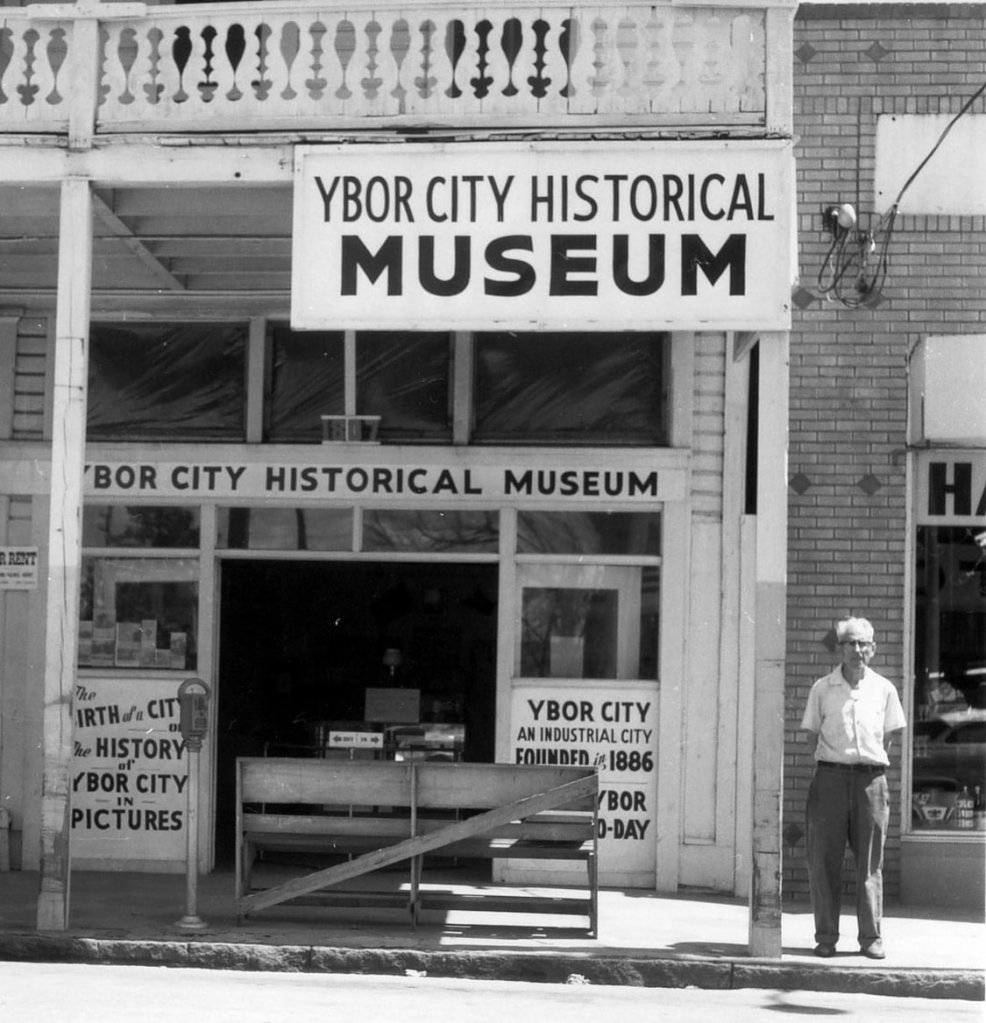

Emilio del Rio standing outside the Ybor City Historical Museum.

By Dayana Melendez

Before the smell of roasting coffee and baking Cuban bread became part of Tampa’s mornings, Ybor City was mostly a promise. In the 1880s, it was little more than scrubland east of a quiet frontier town, a place of dirt roads, alligators and a few scattered buildings. It took a cigar maker with a restless imagination to see something else.

In 1886, Vicente Martinez Ybor, a Spanish immigrant who had built his fortune rolling cigars in Havana and Key West, moved his operations to Tampa. The railroad had finally arrived. The harbor was deep enough for ships. Local leaders were eager to lure industry and offered him land at a bargain. Within a decade, what had been wilderness became a dense immigrant neighborhood filled with Cubans, Spaniards, Italians and Afro-Cubans who followed the work north.

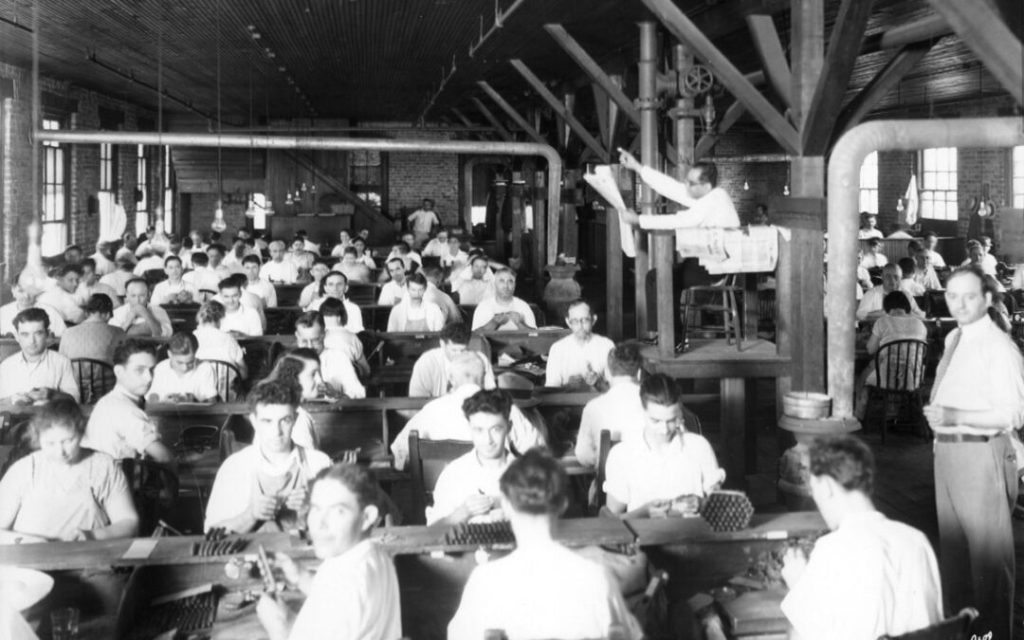

“It was a safe harbor. There were jobs,” historian Gary Mormino told me. “Very quickly, you had thousands of immigrants, entire communities built around the cigar trade.”

Inside the factories, workers rolled tobacco leaves by hand at long wooden tables while a lector sat elevated above them, reading news, novels and political speeches aloud. Outside, life spilled into streets lined with social clubs, cafes and bakeries. In that tight grid of two-story houses and brick halls, a new kind of Latin American city took shape.

A city of coffee, bread and mutual aid

Food and drink were never background details in this world. They were central to how people worked, socialized and imagined their future.

By the early 1900s, Ybor City and neighboring West Tampa were buzzing with cafes and coffee roasters. “The coffee thing is pretty amazing,” Mormino said. “If you look at city directories from around 1910, you see four or five coffee warehouses and roasters in Ybor City alone. For immigrants who grew up where coffee was a luxury, this must have seemed like heaven.”

Coffee anchored daily rituals. Men and women stopped in cafes before long shifts at the factory. Neighbors lingered over small cups in the afternoons. The cafes were as much social clubs as they were businesses.

Alongside them, bakeries such as La Segunda, founded in 1915, began producing long loaves of pan cubano that became essential to the city’s identity. The bread itself was a local invention, baked with a palmetto frond laid across the top.

“We made a bread here that was unique, that you don’t find in Cuba,” said Patrick Manteiga, third-generation publisher of La Gaceta and president of the Cuban Club Foundation. “Without the bread, it’s nothing.”

Paired with roast pork, ham, salami, Swiss cheese, pickles and mustard, the bread created Tampa’s Cuban sandwich, a collaboration born from the city’s mix of Cuban, Spanish and Italian workers.

“For a town to have five unique foods to itself is probably better than most towns could do,” Manteiga said. “Spanish bean soup, deviled crab, the Cuban sandwich, bollitos, crab enchilado. These were combinations of local products with the spices and aromas from Cuba, Spain and Italy.”

Clubs that recreated a lost Havana

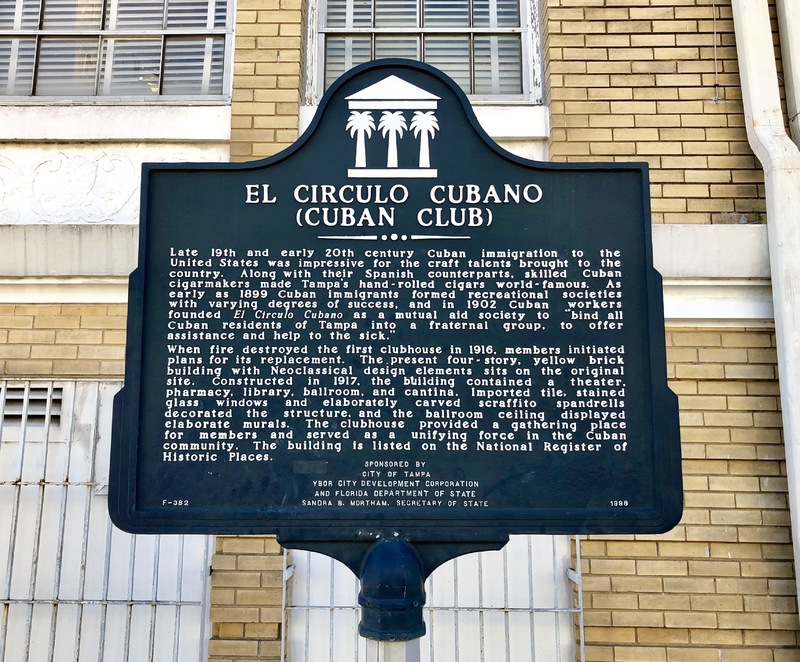

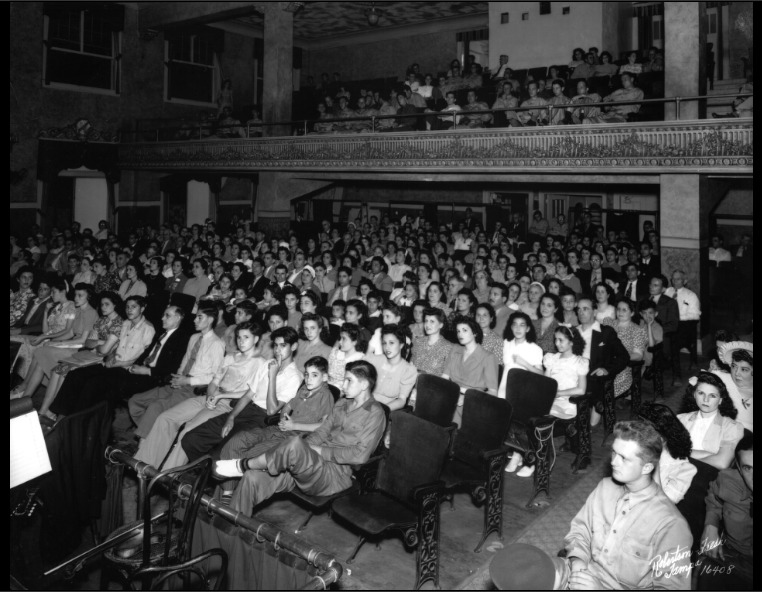

If the factories gave immigrants a livelihood, the mutual aid societies gave them a life outside work. The Cuban Club, Centro Espanol, Centro Asturiano, the Italian Club and the Marti-Maceo Society for Afro-Cubans became second homes.

“The Cuban Club was formed to try and fill the social hole that was left by not being in Havana,” Manteiga said as we sat inside the four-story brick building on 14th Street. His grandfather arrived from Cuba in 1913, and his family’s story is woven into the club’s history.

Havana at the turn of the century was cosmopolitan. Tampa was not. Daily steamships ran between the two cities, which made returning to Cuba possible, but that only heightened the longing for home.

So immigrants rebuilt parts of Havana in Tampa.

The Cuban Club included a theater, classrooms, a library, billiards, a cantina, a women’s room and ballrooms. Members paid small weekly dues and received access to doctors, prescriptions and hospital care.

“We were the first HMO in America,” Manteiga said. “You could have your baby for free, get your drugs for free, have your last dying breath at the hospital for free.”

Spanish societies built hospitals of their own. “How many Americans had medical care, let alone how many immigrants,” Mormino said. “It’s pretty astounding. They were very well organized.”

One big Tampa Latino family

What set Tampa apart from other immigrant enclaves was not only the density of institutions, but how quickly identities blended.

“Nowhere else in America do you find a Cuban club, a Centro Asturiano, an Italian Club, a Centro Espanol, all like this,” Manteiga said. “Other immigrant groups didn’t do this.”

In Ybor, Cubans, Spaniards and Italians worked in the same factories, frequented the same restaurants, attended the same dances and intermarried.

“It’s a Tampa Latino food culture,” Manteiga said. “It’s our own thing that we created here.”

The dishes were designed for factory life: portable, affordable and deeply seasoned. “Most of our food has a carrying case around it,” he said. “The sandwich has bread. The deviled crab has a shell. The stuffed potato has a fried outside. You can eat it in your hands.”

From mutual aid halls to restaurant tables

Many Cuban-owned restaurants that define Ybor and West Tampa today trace their roots back to the neighborhood’s early days. La Segunda still sends out its loaves across the city. The Columbia, opened in 1905, grew from a modest cafe into a landmark that helped introduce Spanish and Cuban dishes to Anglo diners.

“It’s hard to overestimate the Columbia,” Mormino said. “It was probably the first Ybor City restaurant that attracted Anglo patrons.”

Other restaurants, cafeterias and bakeries became extensions of the clubs in spirit. Manteiga still sees the echoes.

“You have this whole situation where this group of men will meet at this restaurant on a Monday, a different group on a Tuesday,” he said. “Groups of women meet at a certain restaurant at a certain time every week. It feels familiar.”

Food remains the excuse to gather. Belonging remains the point.

Tradition, reinvention and what remains

Tampa’s Cuban food culture is surprisingly conservative in some ways. “Black beans and rice never change,” Mormino said. Yet the broader restaurant scene has shifted. The classic sandwich shops that once defined the city are harder to find, and many menus have expanded with modern twists.

“In the 70s and 80s, Cuban food in Tampa was considered a sandwich shop,” Manteiga said. “Everybody offered the same things. Now you see more spins.”

Newer spots, including Flan Factory and cafes across West Tampa, experiment with Cuban-Chinese influences or fusion dishes. Some childhood staples, such as Cuban fried rice, are harder to find.

Still, the core traditions endure.

“I think food reminds us of the past,” Manteiga said. “When you want to think about your mother, the best thing to do is eat something she cooked for you.”

For Mormino, the clearest symbol of the Cuban legacy is Jose Marti Park in East Ybor. The land was donated by the Cuban government, making it the only Cuban-owned property in the United States. The small park honors Marti’s visits to Ybor City in the 1890s and the cigar workers who supported his fight for Cuban independence.

“In Marti’s mind, Ybor was a symbol for Cuba,” Mormino said. “It had problems, but it represented hope.”

In Marti’s mind, Ybor was a symbol for Cuba,

That hope is still baked into the neighborhood’s food. It lives in every loaf shaped before dawn at La Segunda, every cafe con leche poured for someone who has been sitting at the same counter for decades, every deviled crab folded for a festival crowd.

To understand Ybor City is to understand that heritage. It is the taste of home remade, and the story of immigrants who turned labor into legacy and built a community that continues to gather around the table.